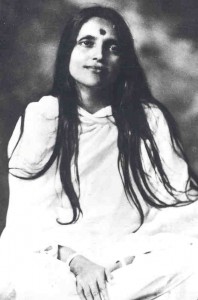

When Swami Kriyananda was living in India as a young monk from 1958 to 1962, he spent a great deal of time with Anandamoy Ma – the “Bliss-Permeated Mother” of whom Paramhansa Yogananda wrote very inspiringly in Autobiography of a Yogi.

Anandamoy Ma gave Swamiji a very unusual amount of her attention. And when he said that he didn’t want to be selfish by taking up too much of her time, Ma replied, “There cannot be selfishness in that which leads to the dissolution of all sense of self.”

When you’re selfish, it means that you’re building up your egoic self-definitions. But to be greedy for spiritual experience is very different. To be greedy for the company of saints, to be greedy for spiritually reminding things, and to want to live in the company of other spiritual seekers – these are the things we were born for, and they cannot be classed as selfish, because they help us become free of our ego-attachments.

Our Bible reading today quotes Jesus’ words: “But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.” (Matthew 6:33)

Most of us haven’t reached a level of spiritual awareness where we could simply walk away from the world. But for those who have reached that level of consciousness, it can be a very valid option: they can go to the Himalayas or enter a monastery, or they can simply go out into the wilderness and have a life apart from the world.

It was several years before I met Swami Kriyananda that I began to understand that spirituality was the right way to live. A friend and I were trying to think of how we could become spiritual people and leave our old life behind, because we had become aware that seeking the kingdom of heaven was the true purpose of life.

It was the spring of 1966 – we were nineteen and typical children of the Sixties, but although we were thinking very seriously about spiritual things, they were still theoretical to us.

We had read the works of Vivekananda and the life and sayings of Ramakrishna, and it was all very powerful and consuming stuff, but we didn’t know what to do with it.

And then, as we were driving on a mountain road near Santa Cruz one day, we came across a man who was hitchhiking. And although we had a strict policy against picking up hitchhikers, the car mysteriously decided that it wanted to pick him up, and that’s the only way I can explain it, because we suddenly found ourselves parked by the side of the road, and the man was stepping into our car.

His name was Stan Trouth. He later went to India and became a swami, and then he returned as Swami Abhayananda. But at the time when we met him he was part of the inner circle of the beatnik movement, with the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the writer Jack Kerouac and those people, and he called himself a “Dharma bum,” as they did.

He was a writer and an artist and a seeker, and I believe it’s why our car insisted on stopping to pick him up, because God wanted to show us what was possible on the spiritual path, beyond the theory.

He had started out in the San Francisco beatnik scene, and then he had become inspired by God. He had found an old, half-finished cabin in the mountains, and he’d made an arrangement with the owner to live there.

He lived with almost no money. He had no steady work, and whenever he needed a little money he would stand on the corner and sell his poetry, or he would get people to donate, or he would do just enough manual labor to buy food and candles, because he had no electricity.

I vividly remember visiting him at his little place and listening to him talk about God. He slept little and meditated late into the night, and he had written spiritual lyrics to many popular songs. So he was someone who had made a real commitment to living differently.

He used newspaper in his outhouse because it was free. And when we brought him some big packs of toilet paper, he politely refused them, saying, “Why would I add something to my life when I have everything I need?”

The first time we visited him, I was playing with the candles, letting the wax drip and make little patterns. And when we visited him again he very kindly and carefully asked me not to do that, because I was wasting the wax.

So he was looking at the world in a different way, and he was a great spiritual friend for the rest of my life, both through his example and his vibrations, and although we lost physical contact long ago, we haven’t lost the inner spiritual bond.

Among the reasons our spiritual community in Mountain View has become a holy place is that Swami Kriyananda spent lots of time there over the years.

He would often give programs when he was in the community, and on one of his visits he gave a pair of satsangs at Chela Bhavan, the house in the community where I live.

The first meeting was for the members of our Sevaka order, which is our householder monastic order, and the other was for our Sadhaka order, which is a lay order for people who are devoted to the religious life, but who have karmas that are keeping them engaged in the world, perhaps related to family or career or whatever it might be.

When it was time for him to give the satsang for the Sadhaka members, he asked me, “What should I talk about?”

I said, “Well, Sir, there’s sometimes a little confusion because people don’t understand what the Sadhaka order is, versus the Sevaka order, and maybe you could help them understand how to be fully dedicated members of a lay order.”

So Swami began the satsang, and pretty soon he was talking about his life as a monk, beginning when he met Master at the age of twenty-two, in 1948, until he was expelled from the monastery in 1962.

Now, in his heart and mind, Swami never left the monastery, because he referred to it until his dying day as a divorce to which he had never agreed.

It was one of the divine plays that were necessary to accomplish the building of Ananda, for which we are eternally grateful. In fact, I’ve often joked that on the anniversary of the day he was expelled we should send a bouquet to the president of that organization in gratitude, because if he hadn’t been kicked out, Ananda wouldn’t have happened.

Nevertheless, it was a tremendous trauma for him, because he had given himself completely. He had turned his back on the world, with no thought of ever returning, and there was nothing in him that wanted a life outside of the monastery. But God had other plans.

When they put him out on his own, his parents took him in and supported him. He was thirty-six years old, and he was separated from everyone he’d known who had mattered to him. After fourteen years of monastic life he had no other friends in the world, and to everyone who’d been close to him he was now persona non grata. He had no money beyond a few hundred dollars, and no spiritual companions, and all he had was Master. And he clung to Master with absolutely everything he had, because he would not give up his discipleship.

It was a crisis of discipleship, because everyone he had trusted, and that he had believed were there to guide him and were in tune with the path, as he was, had suddenly declared him an unworthy disciple and had cast him out.

So he was completely alone with Master, and there could be no more fitting example of the need to seek the kingdom of God first. Because God will give us these great tests to challenge us to look deeply into ourselves and ask: “What is of value to me? Who am I? What do I believe?”

It’s easy to say that we have faith, because just look at all the ways God is supporting us. But it’s quite another when you find yourself living an extremely harrowing version of the Book of Job, where everything that you hold dear is taken away from you, and all the things you’ve been depending on as evidence of God’s grace are removed.

This is when who we are as spiritual beings gets tested in the cold and often very harsh light of day. And this is why the idea of seeking the kingdom of God first is something we need to practice all the time, no matter how abundantly God is blessing us.

Even if we find ourselves living in a palace, amid great wealth and comfort and good fortune, and even if we’re enjoying the blessings of living in a spiritual community, we will be challenged to question: “What am I truly seeking? Am I here only for the favors that God can give me, or am I here because I have no other reality but Him?”

And so in every situation we must ask ourselves: What am I really doing? What am I looking for? What is the power from which I draw my strength? Am I seeking God in every circumstance of my life?

We may sometimes find ourselves tested on the path, or sometimes not. But that was the position that Swami found himself in, where the only thing he had left was his discipleship. And I marvel that Ananda, and the thousands of people around the world who’ve been drawn to Master and who’ve been inspired and helped by this work, all started with Swamiji finding himself alone with his discipleship. And then all of these things were added.

I had a strange experience years ago when I was visiting my parents in Southern California. I became ill with a very high fever, which was quite unusual for me, and the fever was so extreme that I became delirious. I remember lying in bed curled up in a fetal position, because I feared that if I uncurled my four limbs they would break apart from my body. So I had to remain completely still and keep clutching my body. And of course it was delirium. And as the fever began to fall I was able to reason that there had been many times when I wasn’t in the fetal position and my body had remained intact. So I very gradually and gingerly began to spread my limbs until I realized that I could do so without danger.

I was sitting on the couch watching television with my parents, and I was still in that confused state, but a little bit better. And then I had the thought, “Oh, I’ll just tell them that I’m never going back to Ananda, and I’m going to stay here and get a job and I’ll live with them.”

And I realized that if I said those words my parents would say, “Oh, that’s lovely.” Because it’s not as if they disapproved of Ananda, but they were sort of waiting for me to be done with it. So it would have seemed perfectly natural to them if I had said it. And I had a vague feeling that in another part of the universe there would be great consternation, because this would not seem like a natural thing for Asha to be doing. And the image that came to my mind was of a little thread that started where I was sitting and ran all the way back to my spiritual home at Ananda and my friends and Swamiji. And because of my illness it was a very thin and delicate thread, and I saw demons with their fingers hooked around the gossamer thread, and they were bouncing on it and trying very hard to snap it. And they had affected me to such an extent that I was actually thinking about saying something like that. But I was fortunately able to remember that this was not a sensible idea, and not what I really wanted to do.

Now, that was a momentary test that was quite interesting to me, although it wasn’t actually life-threatening.

But there was Swamiji, lying on his bed and completely alone. His parents were supportive, but they had never really understood what he was doing. He was thirty-six, so it wasn’t too late to start over and do something else, and demons were bouncing on his discipleship and testing the strength of it.

But Swami was adamant. He felt that he might have failed Master, and that Master might even be profoundly displeased with him. And of course that was his greatest fear: that the opinions of those who’d expelled him were actually Master’s opinion. And that would have been devastating to him, because if the Guru is pleased it makes no difference what the world may think of you, but if the Guru is displeased all the praise of the world means nothing. And that was the extraordinary experience that Swami had to go through. And what else could he do?

There was no other way. Because, “Seek ye first the kingdom of God.” And so the great question became, “My life has been given in service to Master, and how am I going to serve him all by myself?”

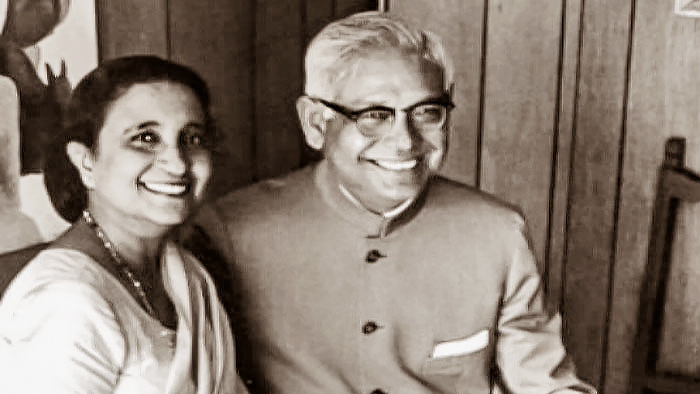

And then, as Swami tells the story in The Path: My Life with Paramhansa Yogananda, God sent Dr. Haridas Chaudhuri, a disciple of Sri Aurobindo. And Dr. Chaudhuri took Swamiji under his wing and helped him get through it.

And before very long Swamiji found himself driving around in his father’s car, teaching here and there, and because he was still an impoverished monastic his father wanted to give him the car to help him get reestablished. It was a very generous offer, and Swami needed to continue to use the car all the time, so there was no way he could refuse it.

But as he was telling the story to the lay disciples, he was weeping. Toward the end of his life he wept often, but in those days he seldom wept, and to see him with tears running down his face was almost unheard-of. And even though the story happened thirty or forty years earlier, tears were running down his face as he told it. He said, “I cannot begin to express to you what it meant to me to have to own a car.” He said, “Because I’d given everything to Master, and now I had to own a car.”

And as we were listening, we didn’t know what to think. But Swami accepted the car, because he knew that it was needed to carry out the commission that Master had given him.

Swami had to earn his own living, and over the years he would earn millions of dollars. I often say that his life would have been the greatest rags-to-riches story, except that he ended up with nothing, because he made money and gave it all away. So it was a rags-to-rags story, and that’s how he built Ananda. None of it was for him, and it was a magnificent illustration of the results of seeking the kingdom of God first. And that’s the only thing that matters, because then everything else that you most earnestly want, which is the uttermost heights of happiness and fulfillment, will come to you.

Of course, most of us would weep with delight if somebody were to give us a car. But Swami’s feeling was the opposite.

And when he finished speaking, he turned to me and said, “Is there anything else that I should be talking about?”

I had asked him to talk about what it means to be a member of the lay order, and he had told us a story of the most extreme renunciation we could imagine. So, in a small voice, I said, “You could talk about what it means to be part of the lay order.”

And then Swami became exceedingly grave. He said, “That’s all I have been talking about.” And of course I looked completely bewildered.

And then he turned to the people in the room and he said, “Don’t even try to live the way that I live.” He said, “You would never be able to do it, and it isn’t even appropriate for you to try.”

Now, I’ve had to meditate on that for a long time, and it has become one of the most important things I understand. “It wouldn’t even be appropriate for you to try.”

Because a fundamental principle of the spiritual path is that we have to overcome the ego, and we have to overcome the real selfishness in us, which is the feeling that I want to appear more important and better than I actually am.

We have this wonderful picture that’s been given to us of our potential on the spiritual path, and what it’s like to achieve the final perfection. But the art of it is just as important as the science.

In Swami’s book on Raja Yoga, he doesn’t call it “the science and the art of yoga,” but “the art and the science.” Because the science is a given – it’s all laid out for us in the scriptures: “This is who we are going to be, and these are the steps to get there.” But to travel the great distance from where we’re standing to that which we most deeply want is the profound art of it.

Dr. Lewis, Master’s first disciple in America, was longing for an experience of samadhi, and he kept pestering Master to give it to him. And then Master turned to him one day and said, “If I gave it to you, could you take it?”

Dr. Lewis had to say very meekly, “No, sir.” Because just because we want it doesn’t mean that we understand what it is, or that we could take it.

I want to be a Nayaswami. I want to be a Sevaka life member. I want to be a complete renunciate. And it’s fine that we want it, but we don’t just need to be looking toward the far horizon, we also have to look at the ground beneath our feet, right here where we’re standing.

We have to look around at the world that we’ve created for ourselves. And there is always a way forward and a way to keep seeking the kingdom of God. But we have to seek it in a way that is wholly appropriate and realistic and fully engaged with our present reality.

We like to imagine that we’ll make faster progress if we can just skip over some of the pieces in the middle. But that isn’t true. “Don’t even try to live the way I do,” Swami said. “Because you wouldn’t be able to do it, and it wouldn’t even be appropriate for you to try.”

So what we have to do is settle for that which has been given to us, with deep, humble faith in God.

Somebody asked me recently, “What does it mean to surrender all our desires to God? What does it mean to surrender our problems to God?”

And of course we talk about it all the time in the spiritual life. But I had to give it some thought, and this is what I came up with. In my heart I talk to Swamiji. And other people may talk to Divine Mother or Master or Babaji or the angels. But I talk to Swamiji, and this is what surrender sounds like to me. “Sir, what are we going to do about this?” Because that’s what it all comes down to.

I wish that I were different. I wish that I didn’t have this sorrow. I wish that I didn’t have this desire for revenge. I wish that I could give up this longing, and this loneliness. I wish that I didn’t have these worldly ambitions. I wish that I wasn’t so lazy.

Whatever it might be – “Sir, what can we do about this?” Because we are seeking the kingdom of God and his righteousness, but this is what we’re presently carrying with us. And, Lord, how are we going to get there?

We know where we’re going, and we know what the journey is like, but we need to hold onto the hand of God all the time, without feeling embarrassed, without feeling ashamed, and without becoming impatient.

Just say, “Sir, what are we going to do about this?” And then listen to what he tells you.

And so, inch by inch, little by little, we move forward.

Swamiji lay on his bed in his parents’ house, and he said that he stared at the ceiling and prayed to die. And that’s what he was offering to God with his prayers: “Master, what are we going to do about this?”

And Master began to answer him, “Hm, how about this? How about this? How about this?” And the rest is history. But it’s not, because the rest is eternity. And for each of us it is the same. God loves each of us just the same, and He will help us find the way.

God bless you.

(From Asha’s talk during Sunday service on October 18, 2020.)