A talk by Asha Nayaswami in Mumbai, India on September 20, 2019. (The talk is long, at 10,000 words. Click here to download a PDF for offline reading.)

While I’m aware that Paramhansa Yogananda urged his disciples to aspire to nothing less than the state of irreversible freedom in God in this life, I’ve never actually felt that his counsel applied to me. I’ve never expected to become a jivanmukta in this lifetime; in fact, I’ve hardly ever given it any thought.

Partly, it’s because for the major portion of my life I was blessed to spend a great deal of time with someone who had attained the state of jivanmukta. And the difference between Swami Kriyananda and me was so dramatic that it seemed inconceivable that I would be able to extricate myself so perfectly from my desires as to be able to live in that state of self-control and inner freedom which was so completely natural to him.

I would watch myself behave, over and over, in ways that were so different. Yet, at the same time, when I look back on my life, I can see that my time has not been wasted.

I became a devotee at the age of eighteen. I was twenty-two when I met Swamiji, and just before I turned twenty-four I moved to Ananda Village, and never looked back. I never doubted and never hesitated. So, on the one hand, my life looks fairly free, at least from that perspective. But on the other hand, I saw what real spiritual freedom looks like. And it’s not as if I feel the least bit downcast or downhearted about who I am.

I’m sure that all of us, without exception, are painfully aware that we could do better. The haunting feeling of incompleteness is Maya’s trick to try to make us feel uncomfortable with who we are, and to tempt us to feel hopeless, with the result that we might try to seek solace in outward ways.

God knows, I battled with enormous insecurities for most of my life, so it isn’t as though I had the complete contentment of a liberated soul. But, on the other hand, it always seemed abundantly obvious to me that I was doing the best I could. And in a very real and positive sense I am fully aware that it was possible because of my friendship with Swamiji.

Some years ago, a woman came to me and wanted to talk about how she doubted that God loved her. And because it’s a very painful position to be in, I did my best to reassure her. But why would she take my word for it? I tried to help her the best I could, but afterward I gave it serious thought. Because even though I’ve had lots of insecurities, I’ve never for an instant doubted that God loved me. And I realized that it was because I had experienced so much unconditional love from Swamiji, and that having had the experience of being seen by him as a spiritual person had been profoundly reassuring to me.

It wasn’t that he saw me as a saint. Whenever you would bring him a cup of tea, he would say very sweetly, “Oh, you’re an angel!” And, of course, he didn’t mean it literally, but he was always supportive of us.

But it went much deeper. It was that he always believed in us. So I can say at least that much. And I know that it could make you all feel sad, if you haven’t experienced that kind of unconditional love. But, at the same time, it was never personal. It was just that he believed in each of us equally, and he loved us all, and he knew that we would all succeed.

But, for me, it never translated into the thought that I would not need to be born in another body, or that I had no more karma to work out. Because common sense told me that I did.

And so, between what Master said was theoretically possible, and what I actually felt, given my knowledge of myself with all my attachments and longings and fears, it looked as if I wasn’t going to be able to get rid of them right away.

But the other side of it is this – how much longer can it really be? Surely won’t be all that much longer, given the degree of dedication we all have. Because even to find ourselves as serious disciples on this path is a great achievement, because this is a very, very advanced path.

Most people aren’t interested in this path. I was amused when a woman came to several of our Sunday services and then said to me, “I’ve been to a lot of spiritual groups in this area.” She described how it’s such a candy store of spiritual options in Silicon Valley, as Swami colorfully put it. She said, “And they all talk about overcoming the ego, but I’m beginning to think that you all actually mean it.” [Laughs] And she never came back, because it’s one thing to talk about it, but it’s quite another to have to come face to face with yourself and deal with it.

I’ve had some serious arguments on this point with my friends. Because, to my way of thinking, our greatest need is to be able to look at ourselves squarely, and work with ourselves exactly as we are.

Every so often, I’ll make this point in a talk, and then I’ll get a bunch of emails basically saying, “You’re going to undermine the faith of everyone if you keep saying we can’t become a jivanmukta in this lifetime!”

They’ll say, essentially, “Swami said we should aspire to be a jivanmukta in this life, and Master said the same. And how dare you not go along with what they said?”

My answer is that Swami was a jivanmukta, and he looked very different than me. And I don’t want to live in a sweet dream, or spin unrealistic fantasies about what might be possible.

I know what kind of power Swami had to overcome himself, and to put himself aside, and to transcend physical imperatives, and to forgive in the face of great betrayals, and to be calm in the face of tremendous challenges. And I’m not like that. I’m a million times better than I was in the beginning. The special blessing of getting older is that I can look back now and see the Mount Everest of change in myself that has taken place over the years. But the distance between me and Swami is still very great.

It doesn’t mean that I repudiate the possibility; it simply means that I don’t understand how it could happen. It doesn’t mean that it can’t happen, it just means that I don’t understand it. And maybe it’s a teaching that’s too subtle for me.

In our satsang last night, someone said that he wanted to know more about moksha. And my answer was, “So do I!” [Laughs]

Because there’s a huge difference between the words, and the ability to perceive that reality. And, really, I have to be honest with myself. So I’m proposing this as a way of thinking about the question of whether we can become free in this lifetime.

Many years ago, in the 1970s when the Eastern teachings and meditation were flooding the West Coast of America, and the New Age movement was being launched from San Francisco, someone published an article on “The Dark Side of Meditation.”

I don’t remember where it appeared, but the dark side of meditation was that many highly competitive Type A personalities were taking up meditation because they were stressed from trying to achieve their worldly ambitions. And when they took up meditation, because the goal is infinite perfection, they would become even crazier, because they now had a goal that was literally unattainable, and they were stressed by the feeling that they were constantly failing.

So the devil’s trick is that if we’re too concerned with trying to achieve perfection, it can actually undermine us instead of inspiring us. Because, and I’ll speak for myself, I know intuitively that I am not free, and I’m not even sure that if God were to come to me and offer to free me of all my desires, I would say yes. Because those attachments are there, and while I’m theoretically inclined to want to overcome them, I’m not at all sure that I want to overcome them to that extreme extent right now. And so the prayer that, many times, has been most helpful to me is not to overcome this or that desire, but “Help me to want to overcome it.”

I’ve watched myself in challenging circumstances where I’ve had to ask, “Why am I not letting this go?” Because I know that I should be letting it go, but I’m not. It’s a question that hits closer to home, and is a lot more relevant for my spiritual progress than “Will I be a jivanmukta in this lifetime?”

“Why am I not letting this go?” And then I find out who I am. I don’t just find out who I wish I was, or who I might wish I could show to others. This is who I truly am, and if the roots of desire are this deep in me, and if even after all my high philosophy I’m still holding onto these things, then that’s what I’ve got to deal with.

I’ve had to accept what I was holding in my heart. And in many cases I was able to articulate it as “Somebody owes me an apology.”

I make it humorous, because I learned from Swamiji that humor can be very useful to us, spiritually. If Swamiji saw that we were feeling open and receptive, he might joke about attitudes that were seriously wrong, so that when you were tempted to fall into them later, you would remember how you’d laughed about it, and it would be a little bit harder to take it seriously.

When I began to understand the feelings that were deep inside me, and that were expressing my particular karma, I realized that learning to accept them with a certain lightness and a sense of humor was a very useful tool for my spiritual growth.

I usually think that I’m right, and that people just don’t understand me, and that they aren’t listening to me. I have an attachment to my own ideas that is just stunning, and when people reject my ideas I feel rejected on a level that’s completely out of all proportion. But nonetheless, that’s how I feel, and many times, even if it turns out that I’m right, people won’t listen to me. But there’s a deep feeling that I want somebody to make that up to me. And I don’t actually want to feel that way, but that’s not the same as saying that I’m not feeling that way.

And so, if we’re serious about becoming a jivanmukta, we have to start exactly where we are. Because Master’s admonition was not a magic pill. It’s not as if we can let ourselves suddenly be so relieved to discover that Master said it’s possible, and now I’m going to sit here and hope to become a jivanmukta. It means that we need to be extremely aggressive and extraordinarily humble at the same time. Just stunningly humble, so that there is no defense, and no ego, and no need to look good even in the privacy of our meditation.

We have to find the ability to be exactly who we are, and to be perfectly willing to put that in front of God, because there is no other way out of our delusions.

Becoming a jivanmukta isn’t about simply remembering that Master said we can be a jivanmukta, and imagining that at the end of this life we’ll be freed. It’s making an extremely firm vow that, starting from this exact moment, I am going to be fearlessly honest about who I actually am, because it’s the only way I’m ever going to traverse the distance between me and God.

And once you start doing that, you’re on the road to freedom. It’s why I simply don’t care whether this is my last incarnation, or if it will be the next one, or the next. There are several reasons I don’t care, and I’ll touch on them. But once we’re able to come bravely before God just as we are, we are on the road that will take us back to Him.

In a very real sense, all of the energy that we’ve been putting out for so many lifetimes to build up this mask that we wear, of the personality and our little ego attachments – we now have to put out the same energy to take it all apart. And if Master says that we can do it in one incarnation, it just means that we’ll have to put out a great deal of energy, and that’s where our energy will have to go. It will have to go into humility and self-honesty, so that we can actually begin to transcend our attachments.

That’s what we’re trying to do. And once you’re doing it as best you can, what difference does it make if you get there in one lifetime, or two, or a hundred? Whether it will happen in this lifetime or the next, your wishes and opinions about it don’t matter a whit.

Master said that we only have to do one percent of what he said, but that everyone will take a different percent, and it’s why he had to teach so much. And everything that he said, of course, is true, but we have to figure out what’s practical for us personally, and what’s practical for us today. And then we have to work with that, and not pretend that we need to be doing something different.

I’ve seen lots of people use Master’s promise as an excuse for not facing who they really are. As if to say, “Oh, well, I’ll be free at the end of it all, and why should I have to deal with these niggling details?” They’re hoping that they won’t have to face who they truly are. Because it takes great strength to muster the self-honesty to know who we are.

Now, of course, you can flip that around, because the mere fact that we are trying means that we have very good karma. In The New Path, Swamiji recalls how one of his brother disciples, Norman Paulsen, said to Master, “Sir, I don’t think I have very good karma.” And Master said, “Remember this – it takes very, very, VERY, VERY good karma even to want to know God!”

And, even so, we are angels. We are very close to the end, and quibbling over one lifetime seems inconsequential by comparison. Because the incentive for us is that we are very near to being free, and why not just try as hard as we can and leave the rest in God’s hands?

Whenever Swami would mention Master’s saying that we should strive to become a jivanmukta in this life, it never felt very helpful to me. First, because it’s confusing, since I don’t have the foggiest idea what it means to be a jivanmukta. I don’t even know what that state is. At best, I can try to deal with the contrast between myself and Swamiji, and I don’t need the added pressure to pursue a state that I can’t even clearly comprehend.

I don’t need the pressure; so I’ve simply decided that it doesn’t apply to me. And if at the hour of my death I find that it did apply, I’m sure I will say, “Well, isn’t this a surprise?” [Laughs]

I’ve rehearsed the hour of my death quite a lot. Swamiji suggests that each night we make a bonfire of our attachments, which is something that I simply cannot do. I can build the bonfire in my mind, but I would be throwing things into the fire very selectively, and stuffing the rest of them in my pockets.

I just don’t have the strength to do it. But what I have rehearsed is the hour of my death, because I’ve been privileged to be with a number of yogis when they died, and I know what an Ananda deathbed scene looks like.

You have all your friends gathered around you, and sometimes they’re being serious, and sometimes they’re talking about what kind of pizza to order. Sometimes they’re bored, and sometimes they’re talking with you very seriously. Sometimes they’re making jokes about your life, and lots of people are coming and going, and cell phones are going off, and people are doing business off to the side.

I know the whole picture. And, meanwhile, somebody’s dying. [Laughs] The person who’s dying is gradually getting more and more gaunt, and they might interact with you for a while, and then they’ll stop wanting to interact. I’ve seen it – how the person dying is still conscious, but they don’t care all that much anymore, and every so often they’ll smile.

So I’ve put myself in that position a lot, of visualizing my own death. And why would it be so casual? Well, for one, because yogis aren’t afraid of death, and they don’t feel that they have to take it too seriously.

Well, now, I’m talking seriously about the long cycle of our death, and I’ve been through those cycles with dying people that lasted days and weeks. And what I found is that you cannot maintain such an extreme degree of pious solemnity for the entire time. And if the person was awake and wanting to interact with you, they wouldn’t want you to be pious, because they would expect you to be natural.

In our film Finding Happiness I talked about the time when my friend Paula was dying. I was on vacation when we learned that she was in the hospital. We had just landed at the airport, and we didn’t know if she was still living, so we called Paula’s brother Arjuna, and we said, “We’re here at the airport, and what’s going on?”

Arjuna said, “Paula’s been dying to see you!” And then you could hear huge laughter in the room where Arjuna was talking. But then he said, “No, no, Paula is not dying to see you!” And, of course, there was more laughter.

But why not be lighthearted about our death? Because we’re still who we always were. And by the time Paula actually left her body, it was a tremendously sacred occasion and very serious.

When our friend Tushti died, there was just one person with her, but there were three or four times when we thought that she would be leaving, in part because her energy became so elevated and magnificent, and in those moments we were totally serious. She would hardly be breathing, with just a tiny pulse, and every so often her chest would rise and a big yogic breath would come in, and then she would be back with us, and we would laugh. And then we would all wait and go through the cycle again.

So even though it might not seem appropriate to laugh when a person is dying, I know that it is. And it was in that spirit that I would rehearse my own death every night, particularly while I was in seclusion, writing the book Swami Kriyananda: Lightbearer.

Because – why not try? I would go through my karma and ask: “Who am I going to have to apologize to? Who do I hope will come and apologize to me? What phone calls will I have to make? What will I say?” If you want to be a jivanmukta, this is what you have to be able to do, because when you’re liberated you cannot take any of it with you.

When Paula died, her “passing party,” as we called it, lasted three days. Paula had called those of her close friends who lived nearby to come see her, and she had talked with other friends on the phone.

There was a woman with whom Paula had had an altercation that they’d never been able to resolve. The woman had worked under Paula, and she had become absolutely impossible, so Paula had to fire her. She deserved to be fired, but she was never able to admit it, and she remained angry with Paula for ten years.

And now, with her death very close, Paula called the woman and said, “I’ve always regretted what happened between us, that it caused such a separation in our friendship.” She didn’t say “I was right and you were wrong.” She truthfully said, “I’ve always regretted what happened between us.”

Paula had a sweet and earthy way of speaking. She said, “I’d like to think we’re both big enough gals to put it behind us – what do you think?” And by fearlessly telling the truth, she was able to melt away all the antagonism and hurt feelings.

After the call, she wanted a cup of coffee. In the three years that she’d had cancer, many friends had tried to get her to stop drinking coffee, thinking that she might live longer. But she wouldn’t stop, and I don’t think it was the coffee that killed her. At any rate, a friend went out and got her a cup, and because she couldn’t drink it, she put a swab in it and tasted it. Then an expression came over her face as if she was leaving, and someone tried to take the coffee out of her hand. But she closed her hand and said, “I’m not done with this.”

Coffee had been a real issue, because she loved it, and she wouldn’t stop even though lots of people were trying to get her to quit. And then a couple of hours later, she said, “Okay,” and she let it go.

We said, “Paula, is there anything left?”

There was a man named PJ who had died several years before, and he and Paula had been good friends, but they had had a falling out.

“Paula, is there anyone left? Is there anything left that you need to finish?”

“Well,” she said, “once I was so mad at PJ that he sent me a rose bush and I waited a whole month to plant it.”

We looked at each other, thinking, “Oh, my God, please, when I die, let that be the only thing that’s left.”

I said, “Well, Paula, PJ is gone, so you’re gonna have to settle it with him on the other side.” And she said, “I think we can.”

But that’s what it looks like. And Swami said that because Paula had died so consciously, that he felt she was free. And of course we must ask ourselves how close can we come to that.

At the end, there were something like thirty people around her, and we did a ceremony using Whispers From Eternity, and then she took out the supplemental oxygen. A couple of hours later we all woke up, because we somehow knew that she was dying.

When people begin to go, their breathing changes. While they’re still trying to stay in the body, all of their energy is on the inhalation, and then there’s a point when the energy turns around and it’s all on the exhalation. It’s a dramatic shift, and it tells you that they’re trying to get out, and then the final breath is an exhalation.

I imagine that we all heard the shift and knew she was dying. She would exhale, and we would wait, and she would inhale again. And then she said, “This is very hard. You have to help me.” And I believe she said, “God, Christ, Guru.” Jyotish started chanting AUM, and we all chanted AUM, and a few minutes later she left. She was absolutely conscious to the point of knowing the moment she would leave.

Swami said at her astral ascension ceremony, “You don’t die like that unless you are free.”

When she got cancer the second time, she said to me, “Asha, I don’t have the luxury of a single negative thought.”

I said, “Paula, you’re the sweetest person I know, but if you think there’s room for improvement, go ahead.”

“Oh, yeah,” she said, “there’s lots I could improve on.” She was like a little girl – you would never have picked her out of a crowd. But that’s what it looks like to be free.

So how close are we? And how close can we come? Because that’s what it takes. And the other part of it is that we may think spiritual freedom comes by having an aversion to this world. But having an aversion is not quite the same as vairagya – the intense power to renounce all our worldly desires and attachments.

At the end of Swamiji’s life, in the “Easter letter” that he wrote a few weeks before he passed, he said that he had always felt that this world was not his home, and that he had always wanted to be somewhere else.

And you might think, well, that’s a marvelous spiritual attitude, to want to be somewhere else. But in the letter he said, “Now I realize that God is everywhere.” And even though he had said not too long before that he had always been an enthusiastic person, but that he no longer had any enthusiasm for anything in this world, he had become indifferent as to where he was and whether he was liberated. Because even to push that much against where God wants you to be is to hold onto something that we may pretend is a desire for liberation, but is really only a desire to be rescued. Which is not the same.

If we wish to be rescued, it means that we have an aversion. But aversion and detachment aren’t the same thing, and the difference is subtle. We cannot be craving the things of this world; and yet too much rejection is also pushing against God’s will, and it means that we haven’t yet fully transcended this worldly experience.

We have to transcend every experience. We have to be able to see God everywhere. That’s what it is to be free. And then, of course, we can be wherever we’re meant to be, with complete acceptance.

But, you see, the other side of it is that the masters commit themselves to this world. When I was with Swamiji in the early years, one of the things that was very hard for me to understand was that I thought it was spiritual to, in some quiet way, not give a damn. I had the thought that I shouldn’t care all that much about anything, including Master’s work. And I prided myself on that attitude of “detachment.”

I was thinking that I had come to Ananda to be with Swamiji, and I was going to learn from Swamiji, and I was going to become a spiritual person from Swamiji. And, oh, yes, he was building a community, and that was kind of cute, but I was there just to learn from him, and I went on like that for quite some time. Don’t get me wrong, I worked hard, and I had lots of fun, because I like to work, and I like to be doing things. So it wasn’t as if I was just sitting on the sidelines and sneering. But inside, I really didn’t care, because I thought it wasn’t important.

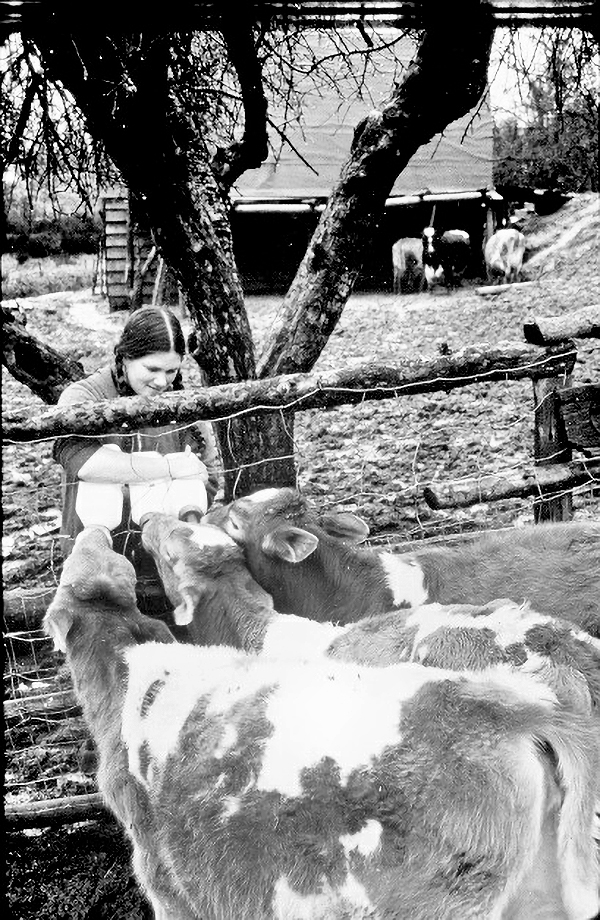

And then one day I was riding in the back of the car with Swami and Seva as we drove through the community. I was looking out at the beautiful land and how we were scratching so hard to get something going, and what an incredibly big project it was, and how every little thing looked like such a great victory.

You would put up a shack that you could put goats in, and it was an incredible victory. So I was noticing that there was a shack here and there, and some tiny little thing happening over here, and I realized that Swami was pouring out his life’s blood to make this community. And then it crossed my mind that here I was, trying to be like him, but I was too “spiritual” to commit myself the way he had committed himself. And I began to think that something was really off inside of me.

So this is another part of how I’ve learned to relate to the question of whether or not I will be free in this lifetime. Swami came to help Master, and I came to help Swami and Master, and that, to me, is what I am about. And if I get liberated in the process, that’s fine. But I kind of consider it their problem, and if they want to liberate me, wonderful, go right ahead. But what I do know is what Master and Swamiji have given to me. And then I look at what matters to them.

You see, Master gave his life for this work, and Swamiji gave his life for this work. And that’s why I wrote 220,000 words about how Swami gave his life to build this work. Because it’s a clue, and a wonderful road map for us all, and maybe we’ll all wake up and realize that this is what it takes to be a jivanmukta.

It doesn’t look like “Oh, well, what do I care?” It looks like I would martyr myself, and I would overcome every personal resistance to do this for Master. And I realized that I am not serving Master by sitting back and thinking about how free I can get. Because I can serve Master best by behaving as he did.

How do you serve your friend? When your friend has a problem, you don’t stay at home and say, “Call me when it’s over.” You dive in and do everything you can to make it work for them.

And so it is with our Guru. It’s a question of asking what matters to him. You can say, “Oh, what matters to him is my liberation.” And that’s true, of course.

But how do we even know what it means to be a spiritual person? That’s what Swamiji did for me. I didn’t have any idea what it was like to be a spiritual person. And so I worked backward from the way he behaved, and instead of working from what I might be thinking, I would work from the way he was. And when I allowed myself to look at it that way, I realized that I’d been coasting, and I was just playing at being a devotee.

You all don’t do the Festival of Light here in India every Sunday, as we do in America, and every chance I get, I campaign for you to be doing it, because it is so filled with divine teachings that will constantly come back to feed and nourish you.

Part of the Festival describes the four stages of our spiritual growth. And in describing the fourth and final stage, it says: “Greater can no love be than this: from a life of infinite joy and freedom in God, willingly to embrace limitation, pain, and death for the salvation of mankind. Such ever has been the sacrifice of the great masters for the world. Here, then, is the fourth and last stage of the soul’s long journey: the redemption.”

And, oh, the fourth and last stage is the willingness to sacrifice everything, including your own freedom, for the salvation of mankind. And this is how the master behaves.

Each time I read those words, I think, “Ah, this is what I’m supposed to be doing, and this is how I can find true freedom. This is how I can become a jivanmukta – I just have to behave as they behave.”

So this is why I’m passionate about Master’s work. I’m incredibly ambitious for Master’s work. I want all hands on deck for Master’s work, because that’s how we’re going to get there.

We are not on a path where we get to go off to the Himalayas. Here you all are living in Mumbai, and a lot of effort is being made, but we have a long way to go before Master’s teachings can take root, because the seed has barely been planted, and who will be ready to till the soil?

It isn’t a question of helicoptering in as I do and declaiming and then leaving again. Mailings have to be done, and phone calls have to be made, rooms have to be cleaned, money has to be raised, and money has to be given. And it’s all in service to Master and Swamiji, from top to bottom.

I was so fortunate when I arrived at Ananda Village in 1971, because I walked onto this big messy piece of land, and there was not much for us to do. You either grew food or you cooked it, or you built buildings. That was about all there was to do, and there was one adult, and the rest of us were children. But he was so much fun.

And then I got to do it all over again in Palo Alto. We went there and had to figure out how we were going to make Ananda happen, and who was going to make it happen, and later, how we could create an Ananda community. And, once again, it was all hands on deck.

But, to me, that is the path to liberation, because I need to become like Swamiji and Master. And, let’s see – how did they spend their lives? And did it give them freedom?

In his commentary on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, Swamiji says: “The best way to overcome the ego is through selfless service.”

I’m guessing that we would all want him to say that the best way to overcome the ego is by renouncing everything and going into my meditation room and doing Kriya Yoga. But that isn’t what he says. Because when we try to get there by meditation alone, the trouble is that we tend to bring too much of ourselves with us.

How can I erase the sense of difference between the two realities – between my service in the world and my meditation? Because that’s how the masters live. They don’t divide their lives.

Swamiji met a man in Canada who lamented that he had so little time for meditation, and he didn’t believe it would be possible to bring God into his work. Swamiji was very distressed by that, because, he said, the majority of the man’s life was not in his meditation room, and how could so much of his life be completely outside his spiritual life?

Now, many of you don’t have the freedom that I have, or that Shurjo and Narayani have, to dedicate all of your time to this work. But everybody can do something. And that’s why I talk about tithing and other ways to serve. Because the best way to overcome the ego is not by saying “This is what I want to do,” but to start humbly serving in whatever ways are needed. And then the right question becomes, “What can I do right now that will help?”

As the Festival of Light says, “Greater can no love can there be than this, from a life of infinite joy and freedom in God, willingly to embrace limitation, pain, and death for the salvation of mankind.”

But that’s not usually what’s being asked of us – it’s not usually pain and death. And yet we have the opportunity to do many things that are within our capacity, and then all we have to do is make it fun.

In Swami’s commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, he says, essentially, “I know that people talk about being a jivanmukta in one lifetime, but, friends, don’t even think about it. Just love God.”

He didn’t say, “Don’t achieve it.” He said, “Don’t think about it, just love God.”

When I read those words for the first time, I said to him, “Sir, this has always been my philosophy, and some of my friends get down on me for it.” Just love God, and know that the rest is in His loving hands.

We think that Self-realization is self-perfection. But Self-realization is self-forgetfulness, which is very different. All of our ideas about who I’m supposed to be, and what I’m supposed to be doing, and what I should give, and how I’m supposed to give it – that’s just more self-preoccupation.

In self-forgetfulness, there is no more self to worry about. And forgetfulness of the little self, and the ability remember the greater Self, comes by always asking, “How can I serve? How can I give? How can I love?” And then, when you’re on your deathbed, it will be so much easier to let it all go, because it’s all you’ve ever thought about, and now God is calling you out of your body, and it’s the same thought of giving everything to Him.

Our attachments and desires are a vibration of consciousness. And it’s not very likely that God is going to come along and rip them out of our hands. Because what eventually changes is our vibration, and if we are simply no longer interested in those things, we won’t even remember that they’re there.

As your consciousness rises with the help of service, Kriya Yoga, and the guru’s grace, your vibration changes, and then what once looked so attractive is no longer attractive at all. And that which your mind was formerly drawn to, you forget that it even exists.

It’s not a question of always having to push ourselves to be thinking, “Oh, I have to advance – goodbye, sweet desires!” It’s that you will no longer even be thinking of them. They will simply cease to exist for you, because you’ve become someone else entirely.

That’s how real spiritual progress happens. Real spiritual progress is not “Oh dear, I wish I could have this, but I need to let it go – and it’s so painful!” I think this is why the question of what it takes to become a jivanmukta leaves people so confused. Because they’re calculating, “If I’m going to be jivanmukta, I’ll have to give up this and this.” And then, with great tension, “Oh, and I’ll have to give up this, too!”

But when you approach it that way, you aren’t really giving up anything, because you’re just creating a whole new set of tensions that bind you to thoughts of the thing you’re supposedly giving

Whereas if we simply love and serve and increasingly want to live like the saints and give back what’s been given to us, it’s a far more natural and happy way to think about our spiritual progress.

That’s how I feel about Swamiji, that if I can do anything to advance the cause for which he gave his life and which was so important to him, because Master had asked it of him and it was his promise to Master – if I can help him keep his promise to Master, then I will feel that I have said “thank you” in a way that truly matters. Because otherwise I’m only taking from him.

That’s what I realized while I was riding in the car with Swamiji and Seva – that this man is giving everything to me, and I’m happily taking it, and what I’m giving back is an occasional cup of tea. And it did not feel balanced, so I decided that I would, at the very least, try to honor the law of gratitude.

Master spoke of how the ideal relationship between the disciple and guru is that of friend to friend. Because the love between guru and disciple is freely given, and it’s based on a shared understanding of spiritual values and of what we are aspiring to do.

It’s why Jesus said to his disciples. “You call me Master, but I call you friend.”

He added, “The servant does as his Master asks, but the servant’s heart belongs to his village.” He was talking about the situation that I found myself in with Swamiji, where the servant does only what the master asks, but it never really becomes his cause.

A friend embraces his friend’s cause as his own, friend to friend. And that is all that we are being asked to do as disciples. We need to be thinking, “This is not Swami’s work. It’s not Master’s work. It’s my work.”

In America we had the luxury and the incredible gift of going through twelve years of litigation, where we had to sacrifice a tremendous amount of our time and an enormous amount of money, $13 million in all, which was raised by three hundred people, almost all of whom were living below the poverty level in America. But we just did it. We gave up everything, because SRF was trying to take away our right to serve Master. And in the process we got to find out how important it was to us.

If someone comes along and takes a little bit here and there, you might not think much about it. But when someone comes and tries to take it all, you are faced with having to stop and ask yourself very deeply what matters to you. And because we had to respond to the challenge, and fight the battle with full engagement, we entered the litigation as children and we emerged as adults, because we had to stand up for our discipleship.

It was a great blessing. It was a tapasya, a spiritual sacrifice for a higher cause. But it was also a great lesson for each of us individually.

It concerns me that if people don’t have the same kind of opportunity, how will they commit themselves wholly to help the work grow, and how will they grow?

I’ve had a unique life, and I’ve often wondered if people could achieve the same results without being able to experience the circumstances of my life?

For some years before Swami died, the access that I had always had to him was suddenly gone. It was no longer available, because in his last years Narayani and Shurjo stepped into that role. There were a few others, but it was just a bare handful.

And what did it all mean for me, and for all of the others who might never have had the opportunity to be as close to Swamiji? I think there are several answers.

Swamiji knew Master for just three and a half years, and virtually no one at Ananda had met Master. So we have a community of people who are devoted to a guru whom they’ve never met. There are many also who are devoted to Babaji, a guru of whom they don’t even have a photograph. Yet somehow his presence lives within them. And somehow the fact of the guru’s physical absence, and the lack of personal contact, doesn’t seem to be an obstacle. Somehow or other, either through the testimony of those who knew him, or from the books about him, or the vibration that comes directly into their hearts, they are able to cross that divide of time and space.

Christianity was created by St. Paul, even though Paul never met Jesus. St. Paul had a life-changing vision of Jesus, when he was traveling on the road to Damascus to kill Jesus and his followers. Jesus appeared to Paul and told him that maybe this wasn’t such a good idea, and maybe you’re fighting on the wrong side. And because Paul became so completely converted, it was his testimony that awakened the world to the fact of Jesus.

There would be no Christianity if there hadn’t been Paul, and Paul was not even a direct disciple; indeed, he was an enemy of Jesus until he converted.

We have to start with the fact that the power of the guru and the Spirit is always there. St. Francis never met Jesus. Padre Pio never met Jesus. Mother Teresa of Calcutta never met Jesus. And not one of them, for an instant, thought that it was the slightest obstacle.

There was a monk in SRF, Brother Turiyananda, who was a dynamic, marvelous man. He had never met Master, so we could say that he wasn’t even a direct disciple. He came to SRF through Swamiji. He was a bit of a rebel within SRF, and he could be outspoken.

There are two stories about Turiyananda that I love. A woman who was a yoga teacher in Los Angeles went to the Lake Shrine where Turiyananda was the minister. She introduced herself saying, “I’m Patricia Reagan. My father is president of United States.” And Turiyananda replied, “I’m Brother Turiyananda, and my Father is the Lord of the Universe.”

Someone came to him and said, “Brother, I don’t see how I can be Master’s disciple, because I need a living guru.”

Turiyananda said, “Master is living. It’s you who are dead.”

So that is the question. And here’s something to think about. These advanced souls incarnate a lot more often than we do, because we are compelled by our karma, whereas they come to help us as often as they need to.

I was at a restaurant with Swami. There were some awful events in the news, and I was saying that if we have to come back to this world, it would be nice if we could come back in a higher age. Swamiji said, almost before I’d finished speaking, “I’m not coming back!” Then he paused and quietly said, “But I know myself. I’ll want to come back to help all of you.”

I said, “Well, that’s why you’re here this time, isn’t it?” And he said, “Well, there is that.”

Our common sense tells us that we have lots of incarnations, but it doesn’t mean that we’re on our own, even if we’re born at a time when the guru isn’t present here.

The inner connection is always there and always unbroken, and even in this world the connection will continue through his disciples. It will go on through Narayani and Shurjo and Jyotish and Devi. And after Jyotish and Devi are gone, and after I’m gone, there will be others who’ve known Swamiji and will pass his spirit on.

And whether you receive that spirit is entirely up to you. The resources are there, through the music, the videos, and the living presence of his disciples. Everything we need is there, and whether we’ll make progress will depend on how important it is to us, and how deeply we attune ourselves to this ray, and how much we let our attunement be diluted by other influences. But it will depend ultimately on how one-pointed you are in your concentration and your service and your dynamic self-offering, and how much you want to be free.

Within Master’s family there are many smaller families. I’ve met Daya Mata probably more times than most SRF members. It was in terrible circumstances, during legal depositions and in courtrooms. And, with all due respect, I never felt anything from her. But other people feel absolutely about her the way I feel about Swamiji, because they belong to her.

Where I belong to Swamiji, some people belong to Oliver Black, of whom Master said that he was his second-most spiritually advanced male disciple, after Rajarshi Janakananda. Sister Gyanamata had her disciples, and Rajarshi had his. We are families within families, and if we want to grow, we must recognize where we are, and accept the circumstances in which God has placed us, and apply ourselves completely.

Nothing is automatic in the spiritual path. That’s the good news: that it’s in our hands. But it’s also the other news, that nothing is automatic, and therefore a great deal is asked of us.

A comedian in America said, “Imagining that sitting in church will make you a Christian is like going into your garage and thinking it will make you a car.”

You can sign up and take all the initiations. You can go through levels one, two, three, and four, and still have nothing, because it doesn’t ultimately matter. Or you can do none of it and have everything, although I advise you to learn from those through whom God can help you.

We will either receive it or we won’t. And that’s the good news, that it’s in our hands.

A lot of people have told me how real Swamiji has become for them, just as people will often say how real Master has become. Since Swamiji’s passing many people have told me that he’s even more accessible, because his body was a limitation, and it’s no longer there.

Many people have told me that he’s more real to them than ever, even more so than when they met him. And, again, I just have to say, how interesting.

Toward the end of his life, he withdrew, and even as Narayani and Shurjo were with him all the time, many of us were farther removed, because he stopped telephoning and emailing, and he didn’t travel as much. So we’ve all had to learn. But I can add my testimony to that of countless others that time and space are not an obstacle. I’m an obstacle. I’m a serious obstacle, but time and space are not.

(Asha answers a question: whether Swamiji was still suffering at the end of his life because of his separation from SRF.)

He had transcended it personally, but he didn’t just walk away from the issues that remained to be resolved. The fact that he persevered in trying to influence them, virtually to the end of his life, was due to the great sense of responsibility he felt for Master’s work.

It was not personal – he was not attempting to restore himself to their graces. It’s a great mistake to think that any part of what happened was personal. It was wholly and entirely a battle for the future of Master’s mission, and Swamiji felt profoundly responsible that Master’s true wishes be carried out.

He never accepted that he’d been kicked out of SRF. As he often said, it takes two to make a divorce, and they may have divorced him, but he never felt that he was divorced from them. To the end of his life, he felt responsible for SRF. He also felt that he was the only living person who could speak to them about the issues, particularly to Daya Mata, because he felt that there were things that Master wanted her to understand.

Of course, she didn’t feel the same way about him. But he felt that way about her, that he wanted to help her, and it wasn’t personal; it was an expression of divine friendship. It was the opposite of personal. It was an offering of divine love, and he kept trying until the very end.

Also, much of what he said, wrote, and did in relation to SRF was for the historical record, and for the sake of those who would come later, and who would want to understand the principles behind what happened.

So much of what he did was about the principles that SRF and Ananda represent, including the principles that were represented by his expulsion. He also felt responsible to clarify the full meaning and implications for Master’s work of the decisions that were made around his dismissal, including the extremely interesting theological and organizational issues.

At one point he called the Ananda community leaders together to talk about whether we needed to keep talking about SRF. As I recall, we were still in litigation with them, so it really wasn’t an option to stop talking about them. But he said, “There are so many important lessons to be learned.” He said, “They are a perfect example of the usual organizational route,” from which he very seriously wanted to save Ananda.

Most people don’t understand that the issues between Ananda and SRF are theological, so I’ll touch on it briefly. The Catholic church made a fateful decision, when they declared that St. Peter was the first pope, and that all authority and understanding of Jesus’ teachings had to be passed down henceforth from Peter through a series of popes in unbroken succession. The fact that at various times there were several popes is brushed over – if you’re writing the history, you can brush over the inconvenient parts. But the assumption was that all authority needs to come from the institution, and that the institution will declare what’s true. And SRF has taken a very similar approach. Daya Mata’s entire justification was, “I was with Master, and don’t you think I ought to know?”

Swami would say, “Well, Master said this and this, and if you think about it like this, it means this, but if you think about it like this, it means that. And then, on the other hand, here are the options, and if you do this, this is bound to happen.”

He trained us to think these things through for ourselves, and not dismiss other views by claiming a higher authority. He never held up his relationship with Master in an attempt to silence discussion – “I was with Master, I ought to know.” He would say, “Master said this,” and he taught us to think for ourselves.

His entire relationship to us expressed the thought that each disciple has an equal potential to be in tune with the guru, and every disciple has an equal potential to understand, even in new ways, what the guru said.

SRF’s point of view is that the SRF board of directors alone knows. I remember a conversation I had with an SRF member about the lawsuit. When I said something about what they were doing, this person said to me, “Well, if the board of directors says it’s a good idea, that’s fine with me.”

I said, “It’s millions of dollars of the money that you all have donated.”

“If the board of directors said it’s fine, that’s fine with me.”

I could only say, “Okay, we were trained differently.”

It’s a theological difference. There’s great comfort in joining the monastery and always knowing exactly where you stand. And for a lot of people, it’s a fine idea, spiritually, because you can forget everything else. You can turn your back completely on worldly concerns and concentrate on your relationship with God. So it’s not wrong, it’s just different.

But Swami felt that it was a very important difference, because the consciousness of humanity is moving into an age in which religion will be more about the Self-realization of the individual, and less about blind acceptance of dictates and dogmas handed down by the institution.

Swami was determined to serve Master’s work, and because most people couldn’t even begin to imagine how selfless that commitment was, they would often think that it was personal. But it was never personal. It was that I’ve been given this commission from Master, and I understand his work, and I feel that they don’t understand it. I was vice president of SRF, and I was the head of the monks, and they removed me, but I never removed myself.

I saw him on several occasions actually correct the SRF monks. “If I was still in the work, I would be your superior,” he said to them. And then he would tell them something he felt they needed to know. They didn’t like it, but I loved it. And Swami was being completely sincere, because, basically, who else is going to tell you, if I don’t? Swami didn’t fight against what people thought of him; it just didn’t make a difference to him.

Daniel Boone, one of Swami’s fellow monks in SRF, gave a talk at a celebration that SRF held in 1993, during which he told an amusing story about Master.

It seems that Master had gone on a trip, and when he returned he said, “Boys, come on, I’m going to have a meal with you.” So they went down to the basement where the monks’ quarters were, and he said, “What do you have to eat here?” He said, “Do you have any Tabasco sauce?” Tabasco sauce is a hot sauce with vinegar that originated in Louisiana. Then Master sipped some of the sauce from a spoon, and the monks are watching to see how he would react to the hot sauce. Then he said to the monks, “Okay, boys, line up now, and he made everyone taste the Tabasco sauce.” And it was so sweet and so natural and funny.

That’s what Swamiji always told us. He said, “Much has been lost in the way Master has been presented.” Swami actually said to me once, “I’ve never been able to put this in a book because I just don’t know how to say it.” But he told me that Master was just so adorable. He was so completely charming, and he wasn’t at all the sort of stern disciplinarian or distant, otherworldly figure that SRF has made him out to be. Swami said that Master was absolutely lovable, and so delightful, and so at ease.

And that’s what Swamiji was like. He was so completely natural. There was no pretense in him at all. We could laugh about anything, and he was the first to laugh. And he said that Master was the same.

SRF has a large archive of recordings of Master, but they weren’t releasing any of them. And when Swamiji finally got hold of a few recordings of Master in the 1980s from a woman in Europe who had gotten them from Dr. Lewis, we published them. The recordings were of Master just sitting around the living room chatting with people. And in the few recordings that SRF had put out of Master, he was mostly exhorting everybody very formally on public occasions. And it seemed to reflect SRF’s attitude, of wanting to release only the talks that would bolster their authority.

Swami said, “Yes, Master did that sometimes, but mostly he was very fatherly.” He was just very warm and fatherly, and Swami was so pleased with these recordings. He said, “This is Master as I knew him, where he just sat in the living room and talked with us.”

It was only after we published those talks that SRF finally began to release more of their recordings. Swami led SRF in many areas – he would take the initiative and they would be forced to follow. But it really let us feel and know what Master was like, and that he wasn’t at all like these two-dimensional pictures of some great otherworldly figure who’s always declaiming and raining down opprobrium on mankind – those remote images that leave us feeling stranded, and that we don’t know how to relate to because they don’t seem human.

Maybe we’ll all be free in this life. Or maybe when we cross over we’ll discover that we’re much more advanced than we think we are. And wouldn’t that be a nice surprise? I’m all for it. I want it to be registered that I don’t object.

I’ve often said that I hope, assuming I have another body, that everyone will say about me, “She was never a child; she was always an old woman.” I want to carry over the consciousness I have now, with the seriousness, and all that I’ve learned and can understand. I don’t want to waste any time being a child.

My friend Tandava wrote a wonderful poem for me, describing the little girl I might be in my next life, and how everybody will relate to her, and how her toddling steps are the same as an old woman’s. It was very sweet, because he captured exactly what I felt very strongly, which is that I’ll be happy, but I also want to be serious. I don’t want to waste time. So, in that sense, why not accept it? And let’s just get on.

(From a talk by Asha with Ananda members in Mumbai, India on September 20, 2019.)