I don’t check Facebook often, but I’ll sometimes go there to catch up on my young friends whose parents post their darling pictures.

I’m thinking of one two-year-old boy in particular – when I isolate his little face from his age and look into his bright eyes, they seem to have an intelligence of an unusually refined sort, as if he’s looking out at the world from a calm and thoughtful perspective.

Now, I’m sure that if I mentioned this to his parents they would have a lot to say about the other dimensions of his nature.

Swami Kriyananda made a compelling statement about the relationship of parents and their children. “The parents through the physicality of gestation and birth create the physical vehicle through which the soul is able to express its destiny, but the parents create neither the soul nor its destiny.”

The bond between parents and their children is a beautiful relationship of service and gratitude that can unfold in wonderful ways. Yet every child brings his or her own karma, and they are by no means a blank slate.

I was intrigued to hear a friend speak of the struggles she faced while raising her twin boys, because from the moment they were born she was able to recognize one of them as an old friend, and the other as an old enemy.

Master said that while we are drawn together by the compelling force of love, there are also karmas of antipathy or hatred that can draw us together so that we can work out those karmas, which might otherwise bring us together in conflict for many lifetimes.

The fact of reincarnation should be a great comfort to us, because we can be assured that we’ll be able to resolve those karmas in time, and they won’t continue to create painful complexes in our lives forever.

At the same time, it’s good to remember that we are working with very long rhythms. As Swami said, age is the most trivial definition of the soul on its long journey. And while we need to take age into consideration, as well as gender and culture and all of these things, they are trivial in comparison to the great arc of our countless lives.

Looking back over this lifetime, it’s self-evident to me that it’s not my first time on the spiritual path, or my first connection with Swami Kriyananda and Paramhansa Yogananda.

I was talking recently with two young graduates of our Living Wisdom School. The former students often come back to visit, because they enjoy seeing their old friends, including the directors, Helen and Gary, and the teachers who’ve been important to them.

I was chatting with these young people about their experiences in high school, and I confided that I didn’t enjoy high school, because I could never figure out what people were doing with their lives – what their values were, and what was important to them. And it was totally confusing to me.

I’m thinking of one of those basement parties in high school, where they’re playing records, and if you were me, you weren’t being asked to dance. I remember sitting against the wall in the dark, somewhere between laughter and despair, because our lives are tumultuous at that age. And I don’t know how else to put it, but I knew that I was different.

I remember feeling intensely aware that I was from another planet, and that I just didn’t know how to relate. And then a strange thing happened. It was as if an angel and the devil came and spoke to me as I sat there in the dark basement, feeling like the epitome of a wallflower. I felt God saying to me, “I could make you popular, but in order to do so I would have to take away a lot of who you are.” And I said, “No, thank you. I don’t think I want that.”

Now, it wasn’t a difficult temptation to resist, but it was one of the very meaningful experiences of my childhood.

I remember riding in the backseat of the car with our parents when I was perhaps two years old. And my brother, who was older and very clever and really knew how to get my goat, teased me in such a way that we ended up having a spat.

And then my mother, who was a very attentive and good mom, divided the blame equally between us, which I thought was totally unfair. And as she scolded us severely from the front seat, my feelings were hurt. So I crawled down on the floor and curled up in a ball and put my head against the floor of the car and listened to the rumble of the wheels, which was very soothing. And I remember thinking, “The outside of me is upset, but if I keep going deeper and deeper into myself I will find the part of me that is untouched by this experience.”

Now, those are sophisticated words, but however I was able to think about it at two, that’s what I did, and I was able to find the part of me that was untouched, and I was able to calm myself and more or less get over the experience.

So it’s no surprise that when I was eighteen and somebody handed me a book on yoga and Self-realization that told me that my consciousness was inside and that it was entirely under my control, and that my true consciousness was bliss, I only had to read one paragraph before I thought, “This is it.”

It was shortly before my nineteenth birthday, and in all the years since I’ve never had another interest. It took me a few years to move to Ananda, at twenty-four, but I’ve never wavered in what I was doing.

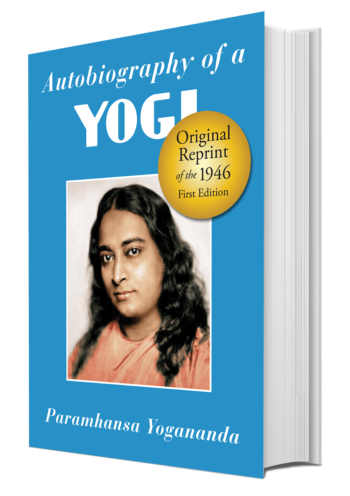

Our reading today includes a passage from Autobiography of a Yogi, about which Swami Kriyananda said that it employs some of the most glorious language in all of spiritual literature.

It describes the moment when Yogananda’s guru, Sri Yukteswar, touches him on the chest and puts him in a state of cosmic consciousness. And with poetic license he tells the story as if it was completely new to him, and it was an experience that he had never had before.

In a paper that Swamiji wrote in the 1980s, “The Way of the Ananda Sanghi,” he gives a statement of what we believe as Ananda Self-realizationists. And it begins, “We believe in an all-pervasive satchidananda.”

“Satchidananda” is the best non-English word I can imagine to replace the very unspecific word “God.” Because “sat-chid-ananda” means the “ever-existing, ever-conscious, ever-new bliss” that most truly defines the nature of the Divine.

And isn’t that a wonderful definition? What is it that we are looking for when we dedicate our lives to God? What is it that we want to experience, more than anything else? What is it that we want to merge ourselves with? And what do we want to be able to share with others and manifest in this world?

I’ve stood here at various times and talked about a peculiarity of my own little brain, which is that the inescapability of consciousness is profoundly disturbing to me, a great deal of the time, and I have to hold myself from wanting to run away, which I believe I’ve done in other incarnations.

People have their own incarnational patterns, and I believe that one of mine has been to drift off into an asylum and talk to beings that aren’t there, in an effort to try to escape from the inescapability of consciousness.

The fact of reincarnation, which is good news for some, is really bad news for others. Because there you go again, and even death isn’t going to take your consciousness away – and sooner or later we must all deal with our lives on the level of consciousness.

When I was young and first setting out on the path, I gradually came to the realization that I would have to deal with my consciousness, and I was very nervous about it, because nobody was helping me with that. Which is why, in the end, I seized upon Self-realization.

All of the people that I had known had tried to help me with everything except that most intimate and all-important issue. And maybe I’m being a bit unfair, because my parents were very ethical, moral, and attentive people, and they helped me become a good person. And of course that’s the first step toward having the right consciousness, to know how to manifest the right behavior and the right attitudes. But the problem of consciousness was unanswerable to me.

I remember a friend who, when he was six years old, began asking his parents about death. And his parents couldn’t answer, because they were nervous about death themselves.

They tried to reassure him by saying that it would be a long time before he would die, and that he would have many happy years. And as he told me, they couldn’t understand that it wasn’t a factor of time for him, but of having his consciousness end, and that he just didn’t know what to do with that.

So they sent him to a psychiatrist who couldn’t resolve it for him either, and it was only when he came on the path of Self-realization that he was so relieved to discover, “Ah – consciousness doesn’t end.”

Now, that was very good news for him, but for me it’s been the worst news, at times, unless I take time to pause and remember that our destiny is ever-existing, ever-conscious, ever-new bliss.

The words “ever-new” are remarkable, aren’t they? Because this world is ever-new all the time. We came into the church this morning, and already we’ve changed so that we are different, because nothing ever remains the same.

People have tried to explain the ever-changing reality of our consciousness by saying that pleasure is merely an interval between two pains, and pain is an interval between two pleasures. Because this life just keeps rising and falling, doesn’t it? And we use the words “attachment” and “non-attachment” to describe the source of our pain, and the solution.

All of our pain, if we examine it closely, comes from the fact that we want things not to change. Whenever we’re presented with something new, we either like it or we don’t like it, and then if it’s pleasant to us we’re unhappy when it goes away. And the cycle just goes on and on.

Ever-existing, ever-conscious, ever-new bliss is the answer. And, just as an aside, there’s a rather astonishing aspect that was brought to my attention by a letter that Paramhansa Yogananda wrote to his chief disciple, Rajasi Janakananda.

Rajasi was always in a state of samadhi, and in the letter Master was giving him suggestions for different things he could do while he was in samadhi, and different ways he could experience the ever-new bliss of the Divine. And how can we possibly understand that? Is it like going to an amusement park for a while, and then going out in the country to look at the scenery, and then maybe you’ll go and enjoy the company of other people? But whatever it is, it’s ever-new, and you’re always conscious.

This world is very different from what it seems to us. But the letter that Master wrote to Rajasi confirmed for me exactly what I realized when I was two years old and I lay on the floor of the car – that no matter what happens, if we can just find a way to go deep enough inside ourselves, we will discover a reality that is untouched, and even more, that is ever-new in its blissfulness.

Even as a child, thank God, I had a light center of gravity, as we call it in Education for Life. And whenever I came to rest, I didn’t sink with heavy consciousness, but I would bob at least a little bit above the surface. Whenever I was pulled down, my natural direction was up, and it was the product of many lives of struggle. And that’s how we get there – not instantly or easily, by any means.

Nonetheless, I tend to bob about in this world, and if I’m not actually standing on top of the water, I’m at least bobbing here and there, and it’s not too bad. It’s enough, and I’m not complaining.

But there’s another aspect of dealing with our consciousness that is reflected in Master’s poem Samadhi, where he talks about the waves of bliss that were bursting over him, and how he was watching all creation, and how he realized that the center of the empyrean was “a point of intuitive perception in my own heart.”

Sextillion galaxies are forming and dissolving, and light years are passing, and the center of the entire experience is a point of intuitive perception in my own heart – not in the physical heart, but in that center of energy in us that defines our individuality and that profoundly determines whether our energy and our consciousness will rise into enlightenment, or descend even further into delusion.

The heart is the point at which those decisions are made. And the heart is where we perceive that God is “center everywhere, circumference nowhere,” as Master put it. Because every living creature and every cell, he said, has that central point of intuitive perception within it.

In one of Master’s affirmations for self-healing, he talks about the tiny mouths of the tiny cells, gobbling up the light. When my friend Paula was dealing with one of the rounds of cancer that eventually took her life, she was very childlike in her spirit, in the highest, most spiritual way, and she loved to visualize the tiny mouths of her individual cells gobbling up the light with conscious awareness.

Master guides us in our efforts to heal ourselves and others, as we make the effort to inspire and awaken the innate intelligence of every individual cell. He shows us how to align the cells with the light force, instead of the confusion that has led us to align our consciousness with a destructive movement of energy.

Everything, including us, emanates from the heart. Jesus says, “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” And what is purity of heart? Some theologies tell us that we are inherently sinners, and that the only thing that will save us is the sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross.

And it’s not entirely untrue. The theology has become a little distorted, but what it’s really talking about is the grace of God through the guru that will liberate you from all delusion. And maybe I can’t defend the whole theology, but the essential impulse is true. The disciples of Jesus knew that he was the messenger of God, and that by the power that he would share with them, they would be able to find the ray of the Divine and rise on it.

The story of Autobiography of a Yogi is about discipleship from start to finish. In the episode that I mentioned, Master stands before his guru, Sri Yukteswar, who touches him lightly on the chest, and he has this tremendous vision.

The story of Autobiography of a Yogi is about discipleship from start to finish. In the episode that I mentioned, Master stands before his guru, Sri Yukteswar, who touches him lightly on the chest, and he has this tremendous vision.

We don’t liberate ourselves. We cannot simply talk ourselves into being free, because the very consciousness with which we’re talking is that which keeps us lost – the rational mind which is mired in the delusion of separateness, and of our identification with the body, and all of the myriad conditions that come about because of that false identification.

It’s fascinating to realize that every time we begin to suffer, how much of that suffering, whether physical, mental, or spiritual, starts from the identification of the higher Self with this limited, much smaller self.

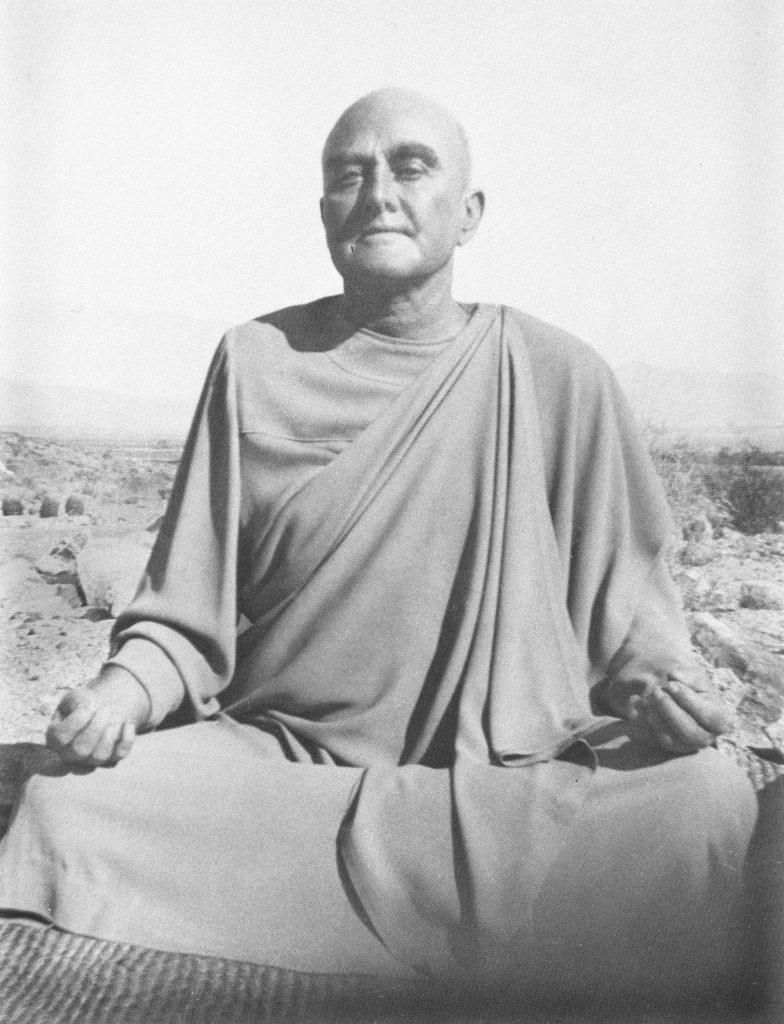

Swamiji was walking with Master one day, holding his arm to help keep him steady, when Master stumbled a little. And Master said, “I am so much in all bodies that I forget which one I’m supposed to keep going.” Now, that is not a problem that I’ve had. And Master said, “I have to ask people whether or not I’ve eaten.”

I tend to remember to have my meals, because I’m identified with this smaller self. But it’s good to remind ourselves that this is not our real Self, and that the entire cosmic creation emanates from a point of intuitive perception in our own hearts. And purity of heart is simply to be who we really are, and not forget it.

Smritti is a wonderful Sanskrit word that means “divine remembrance” – and it matches up perfectly with the term “Self-realization.”

When Master first came to America, he called his organization Yogoda Sat Sanga, which was the name he’d given to his work in India. But he soon realized that offering such an unfamiliar term to Americans in the 1920s would be counterproductive, so he found a name for his work that was based on an existing English term, Self-realization.

Now, “self” immediately turns it back upon us. We don’t call our path “God-realization,” although we might rightly think of it as a synonym. But Master called it “Self,” because the temple of God is within us, and the center of the empyrean is in my own heart. But not “me” as I usually think of myself. And that’s a misunderstanding that people have had regarding the pronoun “I,” as Jesus and other great masters use it.

To whom was Jesus referring when he spoke of “I”? The tiny body that was born of Mary and died on the cross? Or “I,” the infinite consciousness?

What is that greater Self? Looking back to when I was two, and then thirteen, I’m struck that I’m still essentially the same person, even at seventy-one. There’s a consistency that is certainly not defined by my body. And it’s – fortunately – not defined by my mind or my attitudes or my way of life. None of those superficial things define me. And yet the same person is still there. Because, as the Gita tells us, the Self is eternal, and the Self is never born and it never dies.

The Self is ever-existing, and it moves in and out of these bodies, each with its own reality. And so when Master called his work Self-realization, he was asking us to seek the answer to the most central question behind the teachings of yoga, “Who am I?”

And then we don’t need to acquire a great deal of sophisticated knowledge about ourselves and what we are, but we simply need to realize it. And that’s the end of the story – when we realize who we really are.

Sri Ramakrishna gave his foremost disciple, Swami Vivekananda, a vision of who he really was. And then in the vision Ramakrishna took the key and put it in his pocket, and he said to Vivekananda, “I’ll give it back to you at the right time, but in the meantime you have a lot to do.”

Swami Kriyananda said the same of himself. He said that Master told him that he was free, but that he had a lot of work to do, and it wouldn’t be, as Master said, until the end of his life that final liberation would come.

And what does that mean for us, in practical terms? It means that the center of the empyrean emanates from a point of intuitive perception in our own hearts. And purity of heart does not mean that we suddenly need to become really good, to the point where we’ll never take another misstep, or say an ill-considered word, or have a sleepless night, or worry. It means simply to understand that all of these things are not me.

It means to be like the two-year-old child who lies on the floor of the car and listens to the AUM vibrating through the tires, and says, “Yes, I know I’ll have to get up and get along with my brother and be nice to my mother, because there’s no escaping.” And then, at thirteen, “This is not working. I’m going to have to sort it out and deal with it.”

We need to remember these things, at least in some tiny corner of ourselves that will gradually expand until it takes us over and becomes everything, and we finally understand that satchidananda is who we are – the all-pervading, ever-new bliss of the Divine.

And however many experiences it may take, the central fact of who we are can never be taken from us. Because the power of that soul call will draw us back again and again until satchidananda becomes our only reality.

God bless you.

(From Asha’s talk during Sunday service at Ananda Sangha in Palo Alto, California on February 24, 2019.)