“Do I need a guru?” Whenever someone would ask Swami Kriyananda that question, he would reply, “Not if you don’t think so.”

Now, that answer needs to be balanced against the absolute need for a guru, if our desire is to know God. Swamiji would never press ideas on people that they weren’t ready to hear. Nevertheless, the reality is that a guru is essential for those who are deeply seeking their freedom.

There’s a story in India of a saint who had many visions of Krishna. Yet when he asked Krishna to grant him liberation, Krishna replied, “Well, I can’t do that – only a guru can do that for you.” So he sent the disciple to a guru, and a long story ensues. But the point is that there needs to be an intermediary who has been empowered by God to help you dissolve your karma and find your freedom.

Of course, the story raises a big question: if the point is to know Krishna, and you’re having visions of him, why would you need to go through the guru-disciple relationship? Yet the scriptures tell us that it’s only through the instrument of a guru that God can free us.

There was a disciple of Yogananda’s who betrayed him in a particularly egregious manner, turning against him and actually suing him in the courts and taking all his money. And just think of the karma!

For years after the man left, Master would send him a crate of mangoes at Christmas, and every year the man would return it. Master said, “He will never find freedom except through this instrument, appointed to him by God.”

He added that the man would suffer for three more lifetimes, and that he would then resolve that terrible karma and be freed. And in the great scheme of things, three incarnations is nothing.

Having been on this path for forty-five years, I’ve watched people come to Ananda and embrace this path with great enthusiasm and sincerity, and then they lose interest and leave.

Swami used the phrase, “straw fire.” Straw burns hot and fast, but it doesn’t have staying power. People would come here with a great sense that they had found their spiritual path, and then the flame of enthusiasm would sputter and die, and they would be gone.

At a time when Swamiji appointed some of us to help people spiritually, I asked him about this. There were lots of people coming and going through our centers, and it could be a little hard not to take it personally.

Swamiji said, “You have to understand that the karma to seek God for a whole lifetime is very, very, VERY good karma, and not everyone has it.”

We become excited for a while, and then we get distracted by some other shiny bauble, and off we go. And you cannot take it personally, because people will only have as much spiritual karma as they have, and when it’s burned up, it’s done.

They come and they go, and we need to realize that it doesn’t mean that they’re insincere, but that they’ve simply burned up their spiritual karma, and there’s really nothing we can do about it.

I said to Swamiji, “How does this fit?” Meaning, how does it fit within the larger picture of what we’re doing at Ananda, to have so many people coming in one door and out the other? And that was when he said that people will have just so much spiritual karma, so long as they’re still trying to figure out what they want, and what will give them lasting happiness.

Paramhansa Yogananda talked about churchianity, as distinct from Christianity. Traditional Christians imagine that the important thing is to accept Jesus Christ, and then they’ll be saved. And Swami’s wry comment was, “Well, of course, Jesus also has to accept them.”

Our own commitment is part of it, but once the master makes a commitment to us, it’s forever. Think of that disciple who tried to destroy Master’s reputation. When the newspapers got hold of the stories he was telling, they excoriated Yogananda. And of course the nice thing about yellow journalism is that it fades away. But Master couldn’t simply get rid of those trials, because they were an essential and unavoidable part of the disciple’s need to grow in his understanding and work out his karma, and Master wouldn’t allow any inconvenience to himself to deflect his sacred commitment to the disciple.

Master jokingly said of another disciple, James Coller, that he had “commotion karma.” There are people who raise a ruckus no matter how hard they try. When they were building the Lake Shrine in Los Angeles, ducks were coming in and eating the fish, so master got a BB gun to scare them away. One day he fired the gun over their heads, and James made a tsk-tsk sound and grabbed the gun, thinking that Master couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn, and he shot one of the ducks. And, James being James, the incident was witnessed by a neighbor who called the police, and the police came out to see who was killing the wildlife.

Master said that James was like a mouthful of hot molasses – too hot to swallow and too sticky to spit out. He said, “Divine Mother said that he will be liberated in this lifetime. I don’t know how it will happen, but Divine Mother says so, so it must be true.” He had a sacred obligation to his disciple, and he wasn’t above seeing the humor in it. And even when a disciple’s behavior was egregious, as in the case of the man who betrayed him, Master was still responsible for his soul.

So it’s not as if we can lightheartedly decide, “Oh, I’ll be a disciple of this master, or perhaps that one.” Because the choice is not ours, and once we find our destined guru, we have to commit ourselves completely.

The Bible tells the story of a woman who touched the hem of Jesus’ robe while he was talking to a large crowd, and how she was healed of a hemorrhage that had afflicted her for twelve years. Jesus felt her touch because she had called on his help with complete faith and sincerity.

It’s comforting to think that the master is committed to us, but you cannot assume that just because you’ve spoken certain words, “I accept Jesus Christ as my only personal savior” and so on, he’s going to treat you a certain way. It’s not like a worldly transaction, where you give someone a little and then you expect them to feel obligated to you in return.

Master described the guru-disciple relationship as the only one that is free from that kind of bargaining. It’s a relationship of friend to friend, and it has to be reciprocal. It isn’t at all a case of saying, “I’m your disciple, and now you must take care of me.” There has to be a giving on both sides, and it has to be utterly sincere. And this is where service comes into the picture, and why it’s so very, very important.

In my first years at Ananda, I had a tremendous amount of single-minded determination, which I still have. My connection to the spiritual path was entirely through Swami Kriyananda. I had recognized that relationship immediately, and when I came to Ananda Village, I was extremely happy. I was happy to be in the community, and I loved living in the country with my gurubhais. It was a great adventure and a complete lark, and I loved all aspects of it.

Swami put me to work right away in the kitchen, and for a couple of years I made the food, and everything about it was totally fun, even with all the hardships.

We lived in primitive conditions, and the kitchen at the retreat was extremely primitive. I remember coming to work at five in the morning on a winter’s day when it was snowing and very cold. I walked up and saw that the kitchen dome had an extraordinarily beautiful pattern of icicles hanging from the edge of the porch, and I thought to myself, why have I never seen that before? I spent a long time admiring it because it was so beautiful, and then I went inside and saw that the pipes had burst and hundreds of gallons of water had flowed out of the water tower into the kitchen. It was completely flooded, and the water had leaked under the dome and created these beautiful icicles. So I had to figure out what to do, because the water tank was empty.

It occurred to me that the water heater in the bathhouse would still be full, so I made breakfast by trekking through the snow and filling a bucket and carrying it back, and I don’t remember even hesitating, because all I could think of was how beautiful those icicles were. And what difference did it make if it was snowing and the tank had burst and I had to trudge back and forth carrying water?

We had an old truck that we called St. Luke. I think it was an affirmation, because the truck was very far from saintly. Every Thursday, I would load the truck and drive to town to get the week’s supplies and do everyone’s laundry. We didn’t have a laundromat nearby, so I would take twenty bags of laundry and load the truck. The road up the last hill to the retreat was steep, and in the winter it was so rutted and slippery that it was always touch-and-go whether we would make it to the top. The truck didn’t have four-wheel drive, and with the rain and snow, we would generally get about halfway up before the truck would “shoot the road” as we called it. You’d be going as fast as you dared, swinging the wheel back and forth, until you floundered off into the ditch. It took me a while to figure out that nothing really bad would happen when you shot the road. But the truck would flop into the ditch, and everyone would come down and carry the load up the hill. And I don’t ever remember thinking that it was hard. It was a game – how far would we get this time?

How were we able to put up with it? Because we were doing something for Master that was just so much fun. Here we were, at the beginning of this wild adventure of bringing Master to the world and starting world brotherhood colonies, and the idea that we would succeed to the degree that we have today would have seemed ludicrous to us.

At the time, it just didn’t make any difference if there were a few inconveniences. I find it very interesting to look back and see how I thought about it. Because, for starters, I had no responsibility. At least, I didn’t think of myself as having responsibility. I was just a child, spiritually, and Swami was spiritually the only grown-up among us, and there was such an enormous sense of freedom in that way of thinking. And now, forty-five years later, when I seemingly have more responsibility and Swami has left the planet, I ask myself: what’s the difference?

What is the difference? What has changed? Why should I think I’m any more responsible now than I was back then? “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven.” (Mathew 19:14)

Many, many times, particularly in recent years, I’ve said to myself, “What is the difference?” Where did you ever begin to think it was your show?” When you were twenty-four, you knew it wasn’t, and now that you’re nearing seventy, do you think it is? What, if anything, has changed? The buildings have changed, and the meditation retreat has a four-wheel-drive truck, and here in Palo Alto the roads are paved and we have a gorgeous building. But what has changed? And I think it’s a good question to ask ourselves every day.

Why did Jesus urge us to become as little children? Let’s face it, children are really stupid – they’re mostly out of their minds. So we don’t really want to be like little children, because they don’t know anything, and yet, to a certain extent, they are free.

They’re free in their relationship to life. I was watching the children in our Sunday school as they were picking up their crayons and drawing pictures. And I thought to myself, they’re free to be exactly where they are. They’ve come to a place where they’ve never been, and somebody has offered them crayons and pictures, and there’s nothing in the world for them right now but the crayon and the picture.

Somebody offers us a multinational corporation to run, and what’s the difference? It’s the right-sized project for us at the time and for who we are. But have we really ceased to be little children before God? Have we really ceased to be Master’s children? Have we become anything so important that when we get to heaven God will exclaim, “Oh! Here’s the one who ran the big company!” How likely is that? All that matters, and all that we ever experience, is the quality of our consciousness.

Everything in this world conspires to tell us “Now, you must take yourself seriously!” Now, you must have a long face! Now, you must worry! And, believe me, I do worry. I begin to imagine that something bad will happen if I don’t do X, Y, and Z. On the other hand, maybe I’m nervous because something that God wants might happen.

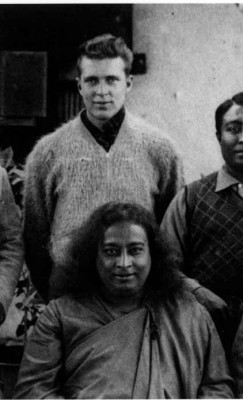

In Autobiography of a Yogi we read the story of Master’s return to India in 1935, which he lets his secretary, Richard Wright, tell in his own words. I suspect he had Richard with him because Master was living so much on other dimensions, and he needed his help to get around. But Richard traveled all over India and Europe with Master, and he describes how, everywhere Master went, he was lauded and honored as the very summit of spirituality. But when Master visited his guru in Serampore, he threw himself at Sri Yukteswar’s feet, and Richard was in awe, because he saw how Master viewed himself, as no more than a child before his own great master.

On a number of occasions, in the sweetest possible way, Swamiji revealed how he saw himself. Toward the end of his life, he became very humorous in his self-deprecation, to the point that I sometimes wondered if it was entirely appropriate. And in response to that thought he simply said, “But it’s fun!”

I remember how, after singing a song for us at Ananda Village, he stepped off the dais, not realizing that his microphone was still on. He was walking away with Jyotish and Devi, and he said to Devi, “Well, time to put the nut back in its shell!” He would talk about himself that way, so impersonally and humorously.

In the early years, it was very, very informal at Ananda. Devi tells how she arrived at Ananda Village on July 4, 1969, and how a man in Bermuda shorts and a Hawaiian shirt walked up and exclaimed, “Oh, we’re having mashed potatoes for dinner!” And then he went eagerly in for mashed potatoes, and she realized later that it was Swami Kriyananda.

Bharat was hitchhiking soon after he arrived at Ananda, and a man pulled over in a VW Bug and drove him to the community. Later, he found out that it was Swamiji, but Swami hadn’t made a point of introducing himself because it just didn’t seem important, and it wasn’t his nature to make a fuss.

As the years passed and many aspects of Ananda changed, people started standing up when Swami came into the room, and I remember him saying, “I feel the myth of Swami Kriyananda swirling around me.” He added, “But inside of it I’m just the same old guy.” And, actually, his concept of himself was always that he was Master’s little boy.

His time with his Guru was just three and a half years, when he was very young. And, in a very real sense, I think it was a blessing, because he always saw himself in relation to his guru as a young boy.

Now, of course, that was his inner attitude. And the more everyone thinks, “Oh, look at all the great things this person has done! Look at how great they are,” the more you realize that it’s all just passing through you, and it has nothing to do with who you are.

I remember how Swamiji would sort of give up trying to explain it to people. If they were wanting him to praise them, or if they wanted him to talk about how great he was, he would quietly say, “God is the doer. It’s what Master wanted, and all I’ve ever tried to do was to serve Master.” And he was always so relaxed and easy and free in that understanding.

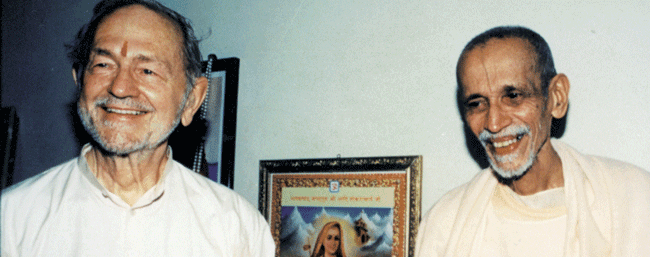

When Swamiji met Swami Chidananda for the first time in Rishikesh, a group of us from Ananda were traveling with him. Swami Chidananda was a foremost disciple of Swami Shivananda. He was president of his guru’s worldwide organization, the Divine Life Society, so he had a position of tremendous responsibility. His devotees were gathered around, and our group from Ananda were hovering around, expectantly waiting for these two great yogis to appear. And then the two of them came out together and sat on a little bench, and Chidananda turned to Swami and said, “And how is Ananda Cooperative Village?” And Swami Kriyananda replied, “It’s fine.” And then Swamiji said, “And how is the Divine Life Society?” And Chidananda said, “It’s fine.” And then they looked into each other’s eyes, and this deep belly laugh started – “Ha ha ha!”

They were laughing with a deep, irrepressible joy. Later, I asked Swamiji if what I had witnessed was what happened – if they had looked at each other and felt, “We know who we are – we are children of our great masters.” Even as a misty cloud was swirling around the myth of Swami Kriyananda, he always knew, I am my Master’s little boy, and that’s all that matters.

That’s what is real. That’s what we need. And that’s what it is to be a disciple, and to have a master. It’s to have the dearest mother and father, and the freedom to be a child in their eyes, and in our own eyes.

Jesus said, “Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.” (Matthew 18:3) And that is the gift that the guru is offering to us, of perfect freedom in God’s love.

(From Asha’s talk during Sunday service at Ananda Sangha in Palo Alto, California on July 24, 2016.)